Weekly Outlook

Recession risks outweigh tightening fears

There were some noteworthy movements in the market this week.

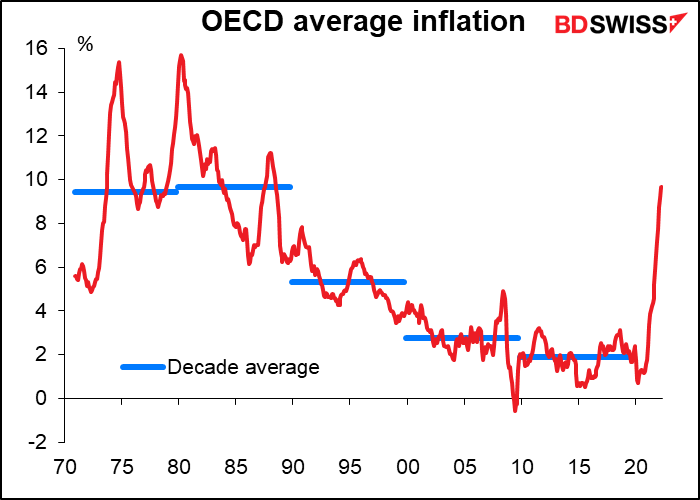

On Wednesday, the European Central Bank (ECB) annual symposium in Sintra, Portugal wrapped up with a panel discussion among ECB President Lagard, Fed Chair Powell, Bank of England Gov. Bailey, and the head of the Bank for International Settlements. According to the FT, Powell and Lagarde said the pandemic and the Ukraine war were reversing many of the factors that had caused over a decade of unusually low inflation and warned that the splintering of the global economy into competing blocs risked fracturing supply chains, reducing productivity, raising costs and reducing growth. “I don’t think that we’re going to go back to that environment of low inflation,” said Lagarde. “There are forces that have been unleashed as a result of the pandemic [and]as a result of this massive geopolitical shock that are going to change the picture and the landscape within which we operate.”

Pretty serious stuff, eh? The days of low inflation are over for good. That means central banks will have to hike rates more and more, back to where they were in the bad old days of rampant inflation.

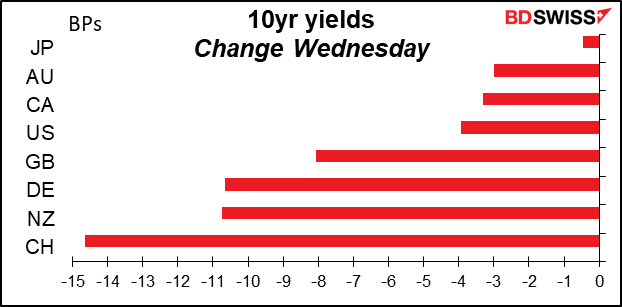

And yet, bond yields and inflation expectations fell nonetheless. Fell substantially, in fact.

Why? Probably because everyone thinks this global simultaneous tightening is going to send the economy crashing into recession.

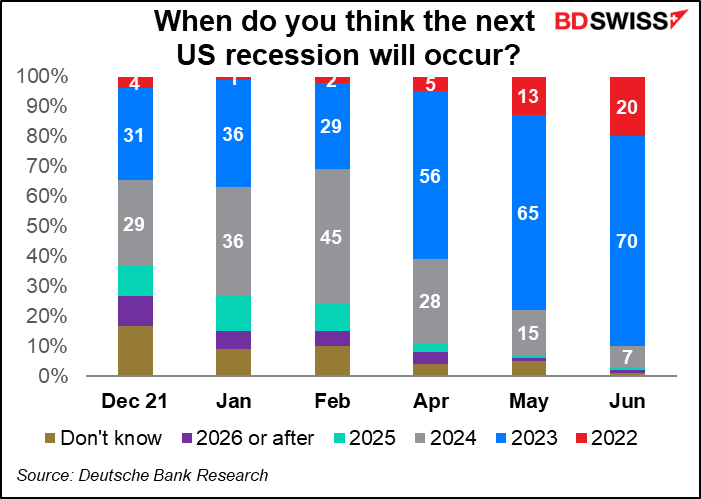

Deutsche Bank recently polled their clients and found that 90% expect a recession by the end of next year, up from 37% at the beginning of the year. Twenty percent expect a recession this year, vs only 2% in January. A the same time, the number of “don’t knows” has also decreased significantly, indicating greater conviction on the part of investors that there will be a recession at some point.

As of Thursday, the 20% voting for this year could be correct (technically, at least). Q1 GDP was -1.6% qoq SAAR. After Thursday’s disappointing US personal spending figure (+0.2% mom), the Atlanta Fed revised down its GDPNow estimate for Q2 to -1.0% qoq SAAR. That would meet the technical definition of a recession: two consecutive quarters of shrinking output.

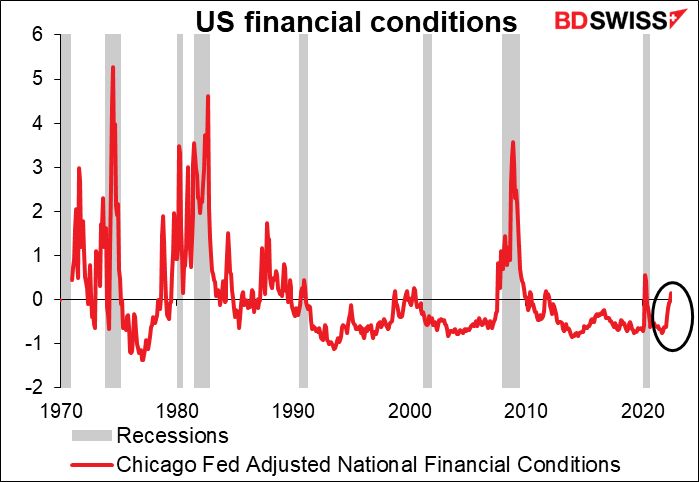

Some indications and symptoms: US financial conditions are tightening – a frequent predecessor to recessions.

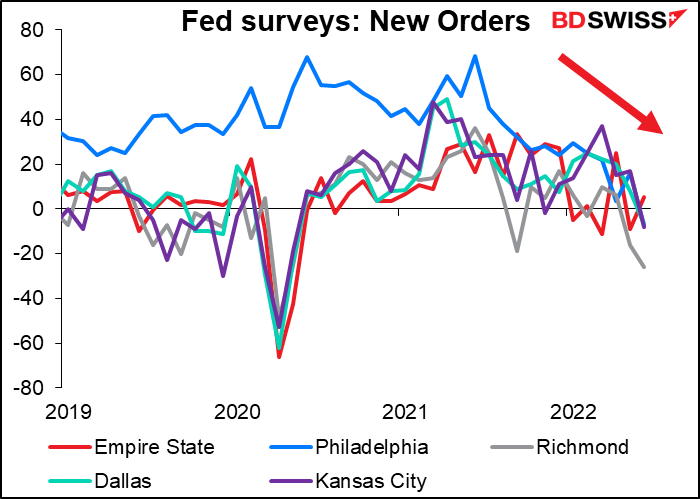

New orders are contracting in four of the five regional Fed surveys.

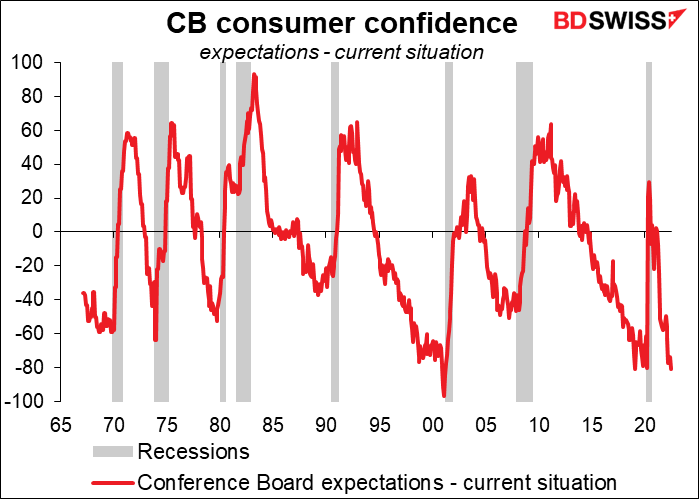

The gap between the Conference Board consumer confidence index for consumer expectations minus current conditions usually falls before a recession as hopes for the future fade. It’s near a record low now.

I’m sure there are a zillion other indicators I could mention, plus another half-zillion that would disprove my point, but the indicators aren’t everything. As Prof. Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein wrote, “Economies and financial markets are social phenomena where beliefs affect reality.” (Trade Wars are Class Wars, pg 196). If people believe a recession is coming, then they will behave as if a recession is coming – individuals will cut back on spending and save more (but not in risky assets), businesses will reduce investment and hiring. These actions will themselves hasten a recession in the absence of offsetting monetary and fiscal policy – which, given the record splurge that governments just ended, is not likely to come to the rescue any time soon. So far businesses are holding up, but consumers are starting to turn over. Watch this space.

Next week: 4th of July, US labor market data, RBA meeting

Monday is the 4th of July! In the US it’s a national holiday commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified on July 4, 1776. The document declared that the 13 Colonies were no longer subjects of Britain but were independent states. Needless to say this is a big holiday in the US, one of the three biggest (along with Thanksgiving and Christmas). Yet it’s shocking how many Americans have no idea what the holiday commemorates.

I’ve lived most of my adult life outside the US. Every year my father used to use the same joke on me, asking ‘Do they have the 4th of July in…” (whatever country I was living in then). (The answer is “no,” then you ask, “Then what’s between the 3rd and the 5th?) I always think of that joke, and him, on this day.

It’s also the first week of the month, which means the US nonfarm payrolls (NFP) are coming out on Friday.

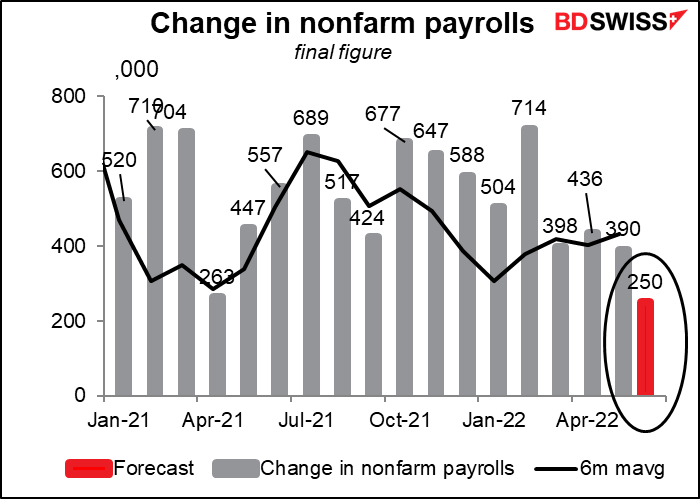

The market consensus forecast for payrolls at this early time is +250k, which would be the smallest increase since +200k in Dec. 2019 (there have been several months when payrolls fell however). This is still a healthy level in absolute terms but it would signify a slowdown in hiring.

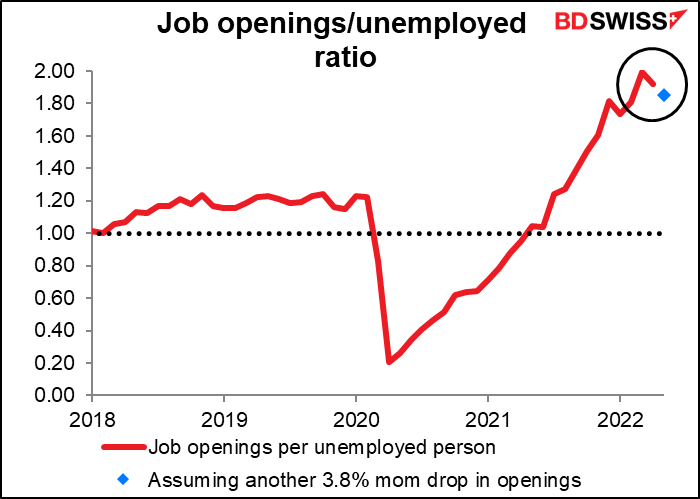

It’s probably not due to any shortage of jobs. The Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for May is released on Wednesday So far no forecasts for job openings, but even if they fall by 3.8% mom again as they did last month, that would still leave 1.85 jobs for every unemployed person – quite enough.

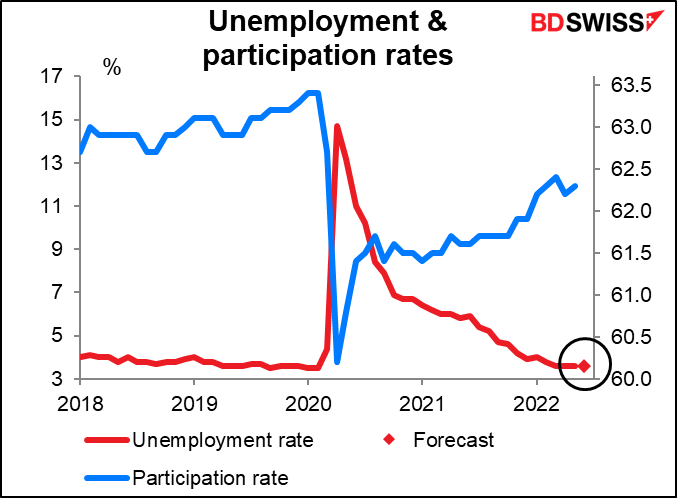

Getting back to the NFP, the reason people watch the NFP so closely is that the US Fed has a “dual mandate” – it’s required to pursue “the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Employment is therefore a limiting factor for their actions – if the US economy gets too far away from “maximum employment” they’ll have to loosen policy. However with the US unemployment rate at 3.6% and expected to stay there for the fourth month in a row, near the 50-year low of 3.5%, I don’t think anyone believes employment is a limiting factor for the Fed anymore.

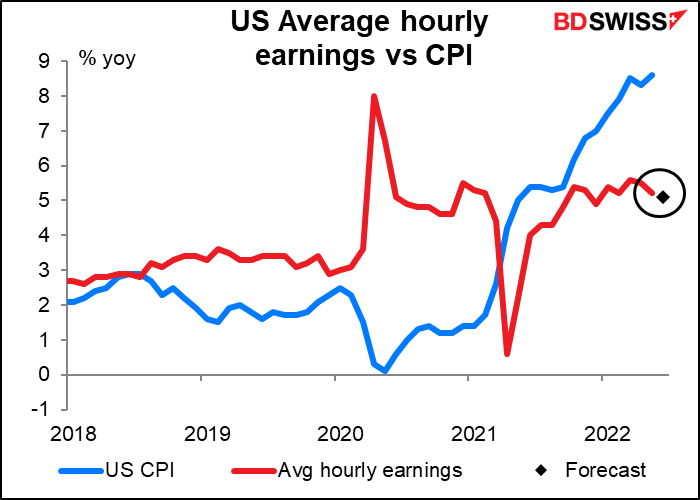

Instead, the Fed is focused on the inflation aspect of its dual mandate. For that reason I think the average hourly earnings are likely to be more significant for the market than the NFP figure itself. One of the things that keeps central bankers up at night is the fear that inflation expectations will become “unanchored,” meaning people will think that inflation is going to be significantly higher than the Fed’s 2% target for a long time, and therefore they have to demand higher wages to keep up their lifestyle. The companies paying these higher wages will then have to raise their prices to pay the higher wages (heaven forbid that their management should take a pay cut or that they should stop their stock buy-backs!). The result would be a wage-price spiral that keeps inflation rising.

Looking at the forecast for this month’s average hourly earnings, there doesn’t seem to be much risk of that. Not only are wages rising by significantly less than the rate of inflation, but the rate of growth slowed in April and May and is expected to slow further. This trend should alleviate some concern that the Fed will have to tighten drastically to get inflation down. That could be negative for the dollar.

Because of the 4th of July holiday on Monday, the ADP report, the harbinger of the NFP, which usually comes out on Wednesday, will come out on Thursday this week.

Wednesday brings the minutes of the June 15th meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Ahead of this meeting, Fed Chair Powell had virtually promised a 50 bps hike and yet they decided to go with 75 bps. The market will be dying to learn more about the reasoning behind that decision and what it might mean for the July meeting (which is seen as having a good chance of a 75 bps hike too) and particularly September. Under what conditions would they high by even more? On the other hand, what would it take for them to revert to the standard 25 bps hikes? The debate at that meeting will shed some light on these crucial issues.

The market is still forecasting another 75 bps hike at the July 27th meeting, but the probability has declined somewhat over the last week.

Other major US indicators out during the week include factory orders (Tuesday), Institute of Supply Management (ISM) service-sector purchasing managers’ index (PMI) (Wed), and wholesale inventories (Fri).

For Europe, the big event is likely to be the release of the minutes of the June 9th meeting. Several important points were decided at this meeting:

- They decided to “end net asset purchases under our asset purchase programme (APP)” at the end of June

- They decided that they had satisfied the conditions in their “forward guidance” and would therefore start raising rates by 25 bps at the July meeting;

- They said they “expect to raise the key ECB interest rates again in September,” with the size of the increase depending on “the updated medium-term inflation outlook.”

- Finally, they decided that “beyond September…a gradual but sustained path of further increases in interest rates will be appropriate.”

Like with the FOMC, the key points will be their reasoning behind the decisions and what might make them accelerate their tightening – or slow the pace. Would they consider hiking by 50 bps in September? 75 bps? What about later in the year? And what might get them to accelerate their planned “gradual” path of hikes? Or slow it, for that matter?

Aside from that, Germany announces its factory orders on Wednesday and industrial production on Thursday. EU retail sales also come out on Wednesday.

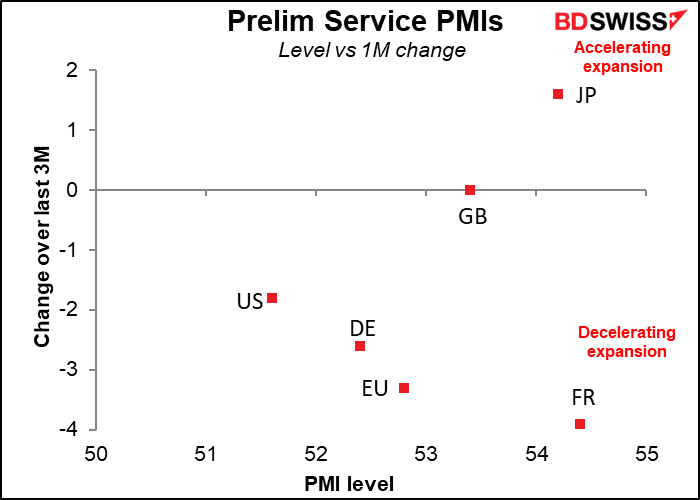

The service-sector purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) will be released on Tuesday, the final versions for those countries that have preliminary ones and the one-and-only for others. (The US ones will be released on Wednesday due to the holiday Monday). The preliminary results showed activity slowing in all the reporting countries except Japan. If the rest of the world follows suit it shouldn’t be particularly good for risky assets or the commodity currencies.

In Japan, the much-maligned labor cash earnings will come out on Tuesday. This should be a big indicator for Japan, the equivalent of the above-mentioned average hourly earnings in the US, but people don’t pay much attention to it, particularly after the agency that compiles the data was found to be using a much smaller sample size than it claimed to be.

Nonetheless I think this indicator could start to be more important for Japan as public perception of inflation heats up and people start demanding higher wages. Talks on increasing the minimum wage began last week at the Central Minimum Wages Council, an advisory panel to the labor minister. The government is seeking a substantial hike of 7.5% to JPY 1,000 an hour or more, but as you can imagine management isn’t enthusiastic. Such a large wage hike would have ripple effects throughout the economy and could cement the inflation rate to over 2%, which might hasten the far-away day when the Bank of Japan starts to normalize policy.

Having said that, the market is looking for an increase of only 1.5% yoy, which would be in line with the recent trend and not indicate any great acceleration due to higher inflation expectations. That could be negative for the yen.

There are no major British indicators out during the week.

Canada releases its employment data on Friday.

There’s only one G10 central bank meeting planned for the week: the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday. The market is pricing in a 50 bps hike at both this meeting and the next meeting, with a good chance of 50 bps hikes at every meeting for the remainder of the year.

RBA Gov. Lowe indicated in a recent speech that the Reserve Bank Board would be debating between 25 bps or 50 bps at this meeting. While there hasn’t been much data since the last meeting (June 7th), Gov. Lowe made it clear in his speech that rates would have to rise further from current levels, which he said were “still very low.” Given that they hiked by 50 bps last month and most other countries recently have also opted for 50 bps (except Hungary, which hiked by 185 bps!), there’s little reason for Australia do to differently.

The next question is, what changes will they make to their forward guidance, if any? I’d expect them to keep their existing vague guidance unchanged. It reads:

The Board expects to take further steps in the process of normalising monetary conditions in Australia over the months ahead. The size and timing of future interest rate increases will be guided by the incoming data and the Board’s assessment of the outlook for inflation and the labour market. The Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time.

They may choose to point to the Q2 CPI release on July 27th as a possible trigger point. Australia is unusual in having only quarterly inflation data, meaning that the RBA is making policy now based on data that’s at least four months old. In the May Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), they forecast that headline inflation would be 5.5% yoy in June and the trimmed mean measure 4.5%. In Q1 they were 5.1% and 3.7%, respectively. If Q2 inflation prints much higher than expected, then the RBA might plump for a 75 bps hike in August. I expect that they’ll want to keep their options open. Retaining the possibility of a 75 bps hike could be positive for AUD.